Mercedes-Benz, through its subsidiary Mercedes-Benz Grand Prix Limited, is currently involved in Formula One as a constructor under the name of Mercedes-AMG Petronas Motorsport. The team is based in Brackley, Northamptonshire, United Kingdom, using a German licence. Mercedes-Benz competed in the pre-war European Championship winning three titles and debuted in Formula One in 1954, running a team for two years. The team is also known by their nickname, the “Silver Arrows”.

After winning their first race at the 1954 French Grand Prix, driver Juan Manuel Fangio won another three Grands Prix to win the 1954 Drivers’ Championship and repeated this success in 1955. Despite winning two Drivers’ Championships, Mercedes-Benz withdrew from motor racing in response to the 1955 Le Mans disaster and did not return to Formula One until rejoining as an engine supplier in association with Ilmor, a British independent high-performance autosport engineering company later acquired by Mercedes, in 1994.

In addition to its factory team, Mercedes currently supplies engines to Racing Point and Williams. The manufacturer has collected more than 160 wins as engine supplier and is ranked fourth in Formula One history. Six Constructors’ and ten Drivers’ Championships have been won with Mercedes-Benz engines.

Mercedes has become one of the most successful teams in recent Formula One history, having achieved consecutive Drivers’ and Constructors’ Championships from 2014 to 2018. In 2014, Mercedes managed 11 one-two finishes beating McLaren’s 1988 record of 10. The record was extended the following year with 12 one-two finishes. Mercedes also collected 16 victories in 2014 and 2015 apiece breaking McLaren (1988) and Ferrari’s (2002, 2004) record of 15. In 2016, they extended this record with 19 wins.

Silver Arrows (1930s)

Mercedes-Benz formerly competed in Grand Prix motor racing in the 1930s, when the Silver Arrows dominated the races alongside rivals Auto Union. Both teams were heavily funded by the Nazi regime, winning all European Grand Prix Championships after 1934, of which Rudolf Caracciola won three for Mercedes-Benz

Daimler-Benz AG (1954–1955)[edit]

In 1954, Mercedes-Benz returned to what was now known as Formula One (a World Championship having been established in 1950) under the leadership of Alfred Neubauer, using the technologically advanced Mercedes-Benz W196. The car was run in both the conventional open-wheeled configuration and a streamlined form, which featured covered wheels and wider bodywork. Juan Manuel Fangio, the 1951 champion, transferred mid-season from Maserati to Mercedes-Benz for their debut at the French Grand Prix on 4 July 1954. The team had immediate success and recorded a 1–2 victory with Fangio and Karl Kling, as well as the fastest lap (Hans Herrmann). Fangio went on to win three more races in 1954, winning the championship.

The success continued into the 1955 season, with Mercedes-Benz developing the W196 throughout the year. Mercedes-Benz again dominated the season, with Fangio taking four races, and his new teammate Stirling Moss winning the British Grand Prix. Fangio and Moss finished first and second in that year’s championship. The 1955 disaster at the 24 Hours of Le Mans on 11 June, which killed Mercedes-Benz sportscar driver Pierre Levegh and more than 80 spectators led to the cancellations of the French, German, Spanish, and Swiss Grands Prix. At the end of the season, the team withdrew from motor sport, including Formula One.

Juan Manuel Fangio at the wheel of the W196 at the Nürburgring during the 1954 German Grand Prix

what does the name actually mean?

Last year’s Mercedes F1 car debuted a brand-new naming structure and this has been followed up by its latest F1 machine: the Mercedes-AMG F1 W09 EQ Power+, which’ll be raced by Lewis Hamilton and Valtteri Bottas in 2018. It’s the team’s second car to go by this moniker, but what does the name actually mean?

It’s part of Mercedes-Benz’s product brand for electric mobility, which was announced back in 2016 at the Paris Motor Show. EQ stands for “Electric Intelligence”, with all future Mercedes-Benz plug-in Hybrids featuring the “EQ Power” designation.

“EQ Power+”, however, is saved especially for Mercedes-AMG future performance Hybrid models. The W08 was the first to proudly go by this name, followed by the Project ONE hypercar. And now, it’s the W09’s turn.

The EQ Power+ designation places the F1 car and its state of the art Hybrid Power Unit at the forefront of the future Mercedes-AMG line-up, showcasing how F1 technology is accelerating the future not just of motor racing, but of automotive technology in general.

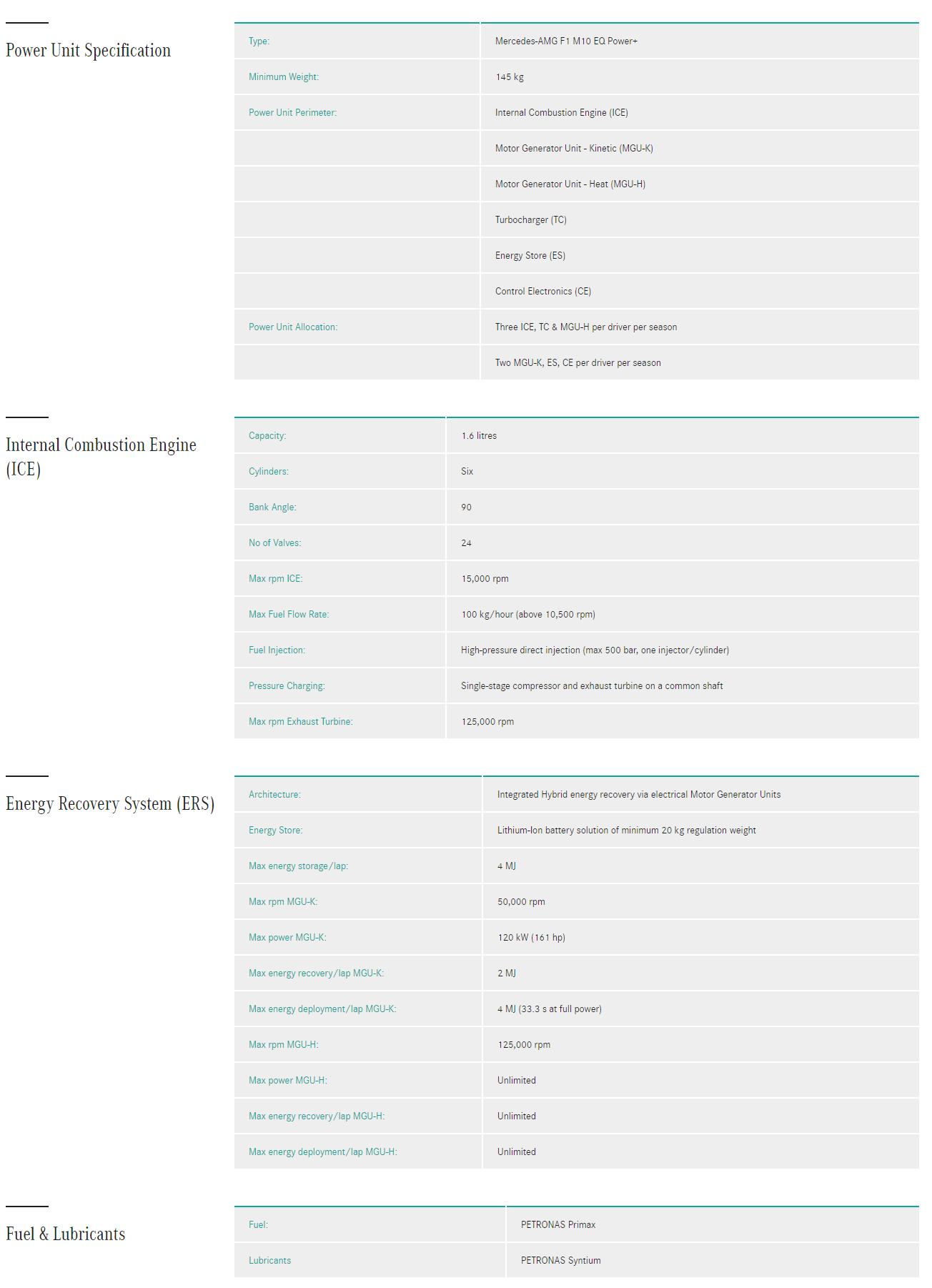

The current set of F1 cars are the quickest the sport has ever seen, largely thanks to a combination of remarkable aerodynamics and hybrid engine technology. The Power Units are made up of six components, which work together to push cars to speeds well over 300 km/h.

Under the bodywork of the new W09, there’s a 1.6-litre Internal Combustion Engine (ICE), MGU-K, MGU-H, Energy Store, Turbocharger and Control Electronics. Drivers are limited to three engines per season, down from four in 2017, which puts further focus and emphasis on efficiency and reliability.

While it’s difficult to envisage the advanced Hybrid technology of these monstrous F1 beasts trickling down to cars on the road, they are very much helping test and develop the technology of the future – what we’ll see in the Hybrid Mercedes-Benz cars and AMG models being driven in years to come.

After all, it’s the perfect training ground, right? Putting this Hybrid technology through its paces at some of the toughest race tracks in the world, at ridiculously-high speeds and in intense conditions. So, while it isn’t always obvious, the influence F1 has on the automotive industry is significant and as relevant as it has ever been.

Lewis Hamilton hails “incredible” new Mercedes as he undergoes first laps in new car

Lewis Hamilton has taken to the track in his new Mercedes car for the first time as he steps up his preparations for his tilt at a fourth world championship.

The Brit braved the blustery, damp conditions brought about by Storm Doris to drive his Mercedes W08 at Silverstone.

His new ride features a narrow rear and adheres to new regulations that are aimed at making the cars faster and more demanding of drivers.

But despite these changes Hamilton was excited to give it a spin.

“Yesterday was the first time I saw [the car] together,” he said. “It is the most detailed piece of machinery I have seen in F1.

“It’s a completely new dynamic,” Wolff said. “I see it as an opportunity to start from square one with a healthy relationship. There are no games, no warfare because there is no history.

“There is a solid foundation that the relationship works well. But you have to be realistic that when they get out there, it is about winning races and championships, and the rivalry could be difficult.”

The first race of the season takes place in Australia on March 26.

MERCEDES F1 DRIVER VALTTERI BOTTAS HAS ‘NO EXCUSES’ THIS SEASON

Mercedes F1 team executive Toto Wolff says Valtteri Bottas has “no excuses” this year as he pushes for a new Mercedes contract.

Bottas had a decent first year with F1’s top team with three wins, but never really contended for the title. He’s planning a full-fledged title assault in 2018.

While he’s only under contract with the team for this season, Bottas said he’s feeling less pressure this year.

“I have gone through one season with Lewis (Hamilton), and the team is now familiar to me. At my best level I can get poles and win races.

“Last February, I had to learn about the team but now I can focus just on improving the performance. I’m able to concentrate on driving a lot more,” he added.

He knows other drivers want his seat, but he will focus only on driving as well as possible in 2018.

“At this stage, contractual issues seem completely secondary,” said Bottas.

“It will only be considered a little later. My goals are so high that they eliminate any external pressure,” he is quoted as saying by Finland’s Iltalehti newspaper. “If I achieve them, there will certainly be no problem with the contracts.”

His teammate and reigning champion Lewis Hamilton isn’t worried about Bottas upstaging him this season.

“But I’d say that about everyone,” Hamilton said in Barcelona. “It has nothing to do with Valtteri.

“He made a great impression in the last races last year and I expect him to be in top form. But I am too,” he added.

AS for Wolff, he expects Bottas to challenge Hamilton in 2018.

“If he can step up and challenge Lewis, he certainly has his place among the best Formula 1 drivers. If he does not, he will notice that there are no excuses,” he said.

The team’s title partner PETRONAS played an important role in the hunt for improved performance and reliability, especially in the development of the new Power Unit.

“The fuel is right at the heart of the combustion and making sure that the chemical composition and the thermodynamic architecture of the Power Unit are working together exceptionally well is key to thermal efficiency,” said Andy.

“PETRONAS have continued to work well with our thermodynamic engineers, we’ve run many candidates on the single cylinder and on the V6 engine to derive a new fuel for 2019. It’s a very tight-knit group, the PETRONAS engineers know exactly how the engine works and our Power Unit engineers know exactly how the fuel works.

“PETRONAS also provide the lubricants for our car which play two roles: to make sure that components don’t contact, it’s key that there is an oil film between highly loaded components both for reliability and for friction reduction. If you can keep components apart the friction is lower, and the wear is lower, but the lubricant also provides cooling within the engine. It’s a critical element of the engine, it’s the lifeblood of the engine for its survival.”

The maximum race fuel allowance has increased by 5 kilograms to a total of 110 kilograms. However, the higher fuel allowance does not impact the thermal efficiency of Formula One Power Units, which are among the most efficient engines ever-built.

“If you have got an efficient engine with efficient aerodynamics and you are prepared to do a little bit of lift and coasting, then you have the opportunity to start the race at less than 110kg,” explained Andy.

“For every 5kg of weight you save, it’s about two tenths of a second a lap quicker, so there is a natural reward to starting the race a little bit lighter. There is still a competitive edge from making an efficient car – both Power Unit and aerodynamics – and racing smartly to make sure that you have good pace at the start of the race as well as through the race.”

Mercedes-AMG F1 M10 EQ Power+ Technical Specification

-

Mercedes-Benz W 25

1934 to 1936

The Mercedes-Benz SSKL, an extremely successful racing car in the 1920s and early 1930s, had served its purpose, driving from success to success. A new age dawned from 1934: the project for the future was the W 25. As to its premiere, Daimler-Benz set its sights on the Avus and Eifel races in the run-up to the French Grand Prix on July 1, 1934, the second of the season. To win the race in France would have been quite a feat, almost exactly 20 years after the one-two-three triumph of Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft (DMG) in Lyon. Eventually, it was an Alfa Romeo P3 Tipo B that actually won the race in Montlhéry, but it was the W 25 which represented the state of the art.

Hans Nibel was responsible for the entire project, Max Wagner for the chassis, Albert Heess and Otto Schilling for the engine. In the testing department under Fritz Nallinger, Georg Scheerer, one of the spiritual fathers of the early supercharged cars built by Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft (DMG), put the machines through their paces. Otto Weber assembled them, while the chassis were put together by Jakob Kraus, both men being veterans of the DMG excursion to Indianapolis in 1923.

The racing engine, even from today’s perspective a highly modern four-valve unit with twin overhead camshafts, to which two blocks of four combustion units complete with cylinder head and coolant jackets were welded, tipped the scales at 211 kilograms. The transmission was flanged onto the differential (transaxle design) to improve the distribution of the axle loads. The supercharger was mounted at its front, providing two pressure carburettors with compressed air. The tank held 215 litres, 98 of which were emptied per 100 kilometres at racing speeds. The four gears and one reverse gear were actuated via a gate with a locking mechanism to the right of the driver’s seat.

The car’s frame was composed of two U-section side members with cross-bracing, all of which extensively pierced for lightness as on the SSKL. The body was hand-beaten aluminium, with a large number of cooling louvers. Aerodynamic fairings enclosed the front as well as the rear suspension, whereas a simple vertical-bar grille fronted the body with its strikingly tapered tail.

The race cars for 1934 were ready by the beginning of May. At dawn of the Thursday before the Avus race on 27 May, Manfred von Brauchitsch, Luigi Fagioli and Rudolf Caracciola took their seats behind the steering wheels of their W 25 cars. In spite of this successful test, the Mercedes-Benz management withdrew the three cars on the grounds that they were not ready for racing yet. Their debut would be a week later in the Eifel race.

Ironically, the 750-kg formula had been created to curb the ever-escalating speed of the powerful racing cars – built for example by Alfa Romeo, Bugatti and Maserati. The very opposite was achieved since design engineers at once resorted to bigger displacements. The Mercedes-Benz technicians had envisaged 280 hp (206 kW) for the initial M 25 A, extrapolating the 85 hp (63 kW) per litre of the supercharged 1924 two-litre M 2 L 8 engine with which Rudolf Caracciola had won the 1926 German Grand Prix on the Avus, and arriving at a theoretical capacity of 3360 cc for the new engine. The actual output of the eight-cylinder engine at the beginning amounted to a massive 354 hp (260 kW). Several engine versions with boosted power output followed. The M 25 AB (3710 cc) variant generated 398 hp (293 kW), followed by the M 25 B (3980 cc and 430 hp/316 kW) and C (4300 cc and 462 hp/340 kW) variants, and eventually, in 1936, the ME 25 version (4740 cc) producing 494 hp (363 kW) – always at 5800 rpm.

The career of the Mercedes-Benz W 25 was brilliant, with 16 victories in Grand Prix and other major races to its.

Technical Specifications

| Displacement: | 3360 cc |

| Output: | 280 hp (206 kW), later boosted to 494 hp (363 kW) |

| Engine: | Supercharged eight-cylinder four-stroke in-line petrol engine |

| Entered in racing: | 1934 – 1936 |

| Top speed: | approx. 300 km/h |

Mercedes-Benz W 125

For the 1937 season, Mercedes-Benz developed a new racing car, the W 125. Its backbone consisted of an extremely sturdy, tubular oval frame made from special steel, with four cross members. It benefited from tests with production car frames as, for instance, the one used on the 1938 generation of the Mercedes-Benz 230. The wheels were located differently, by double wishbones and coil springs at the front, as on the celebrated, noble 500 K and 540 K models, and by a double-joint De Dion rear axle which ensured constant camber, plus longitudinally installed torsion bar springs and lever-type shock absorbers. Lateral links transferred thrust and brake moments to the chassis.

After extensive tests on the Nürburgring, the engineer Rudolf Uhlenhaut came up with a revolutionary suspension configuration: setting a precedent for later Grand Prix car designers, Uhlenhaut just reversed the basic suspension set-up used until then, stiff springing but little damping: the W 125 had soft springs with long spring travel and stiff dampers and thus served as a role model for all modern Mercedes-Benz sports cars. Its outer appearance resembled its predecessor’s, unmistakable all the same by the three cooling air inlets. For the ultra-fast Avus race on 30 May 1937 (Hermann Lang achieved an average speed of 261.7 km/h), it was kitted out with a streamlined body. The transmission and differential formed an integrated unit. The car’s eight-cylinder in-line engine represented the highest evolutionary stage of the Grand Prix machine used since 1934. The supercharger was positioned behind the carburettors and thus supplied with the mixture itself – a first with Mercedes-Benz racing cars.

Although the W 125 served its fast purpose for one year only, it did so with great variability. It could precisely be adjusted to the respective racetrack by means of different transmissions, tank volumes and petrol cocktails, carburettors, superchargers, rim and tire sizes, tire treads and even exterior dimensions. Engine power, torque, top speed and the speeds achieved in the individual gears varied accordingly. As many as eight different transmission ratios were available, for instance, plus two rear-wheel sizes (7.00-19 and 7.00-22). An output of 592 hp (435 kW) at 5800 rpm quoted by the factory refers to the Gran Premio d’Italia in Livorno on 12 September 1937. The engine, which had arrived at a capacity of 5660 cc in the meantime, devoured one litre per kilometre, an aggressive special mixture made up of 88 percent methanol, 8.8 percent acetone and traces of other substances. Ready to race, the W 125 weighed 1097 kilograms (1021 kilograms without driver) in that configuration, including 240 litres of petrol, seven litres of water, nine litres of engine oil and 3.5 litres of transmission oil. The Untertürkheim engineers evoked up to 646 hp (475 kW) from the 222-kilogram engine on the test bench, corresponding to a massive power-to-swept-volume ratio of 114 hp (84 kW) and an equally astounding power-to-weight ratio of 1.16 kilograms per horsepower. Those were values that were surpassed only decades later, just like Hermann Lang’s average speed of 261.7 km/h in that year’s Avus race.

Technical Specifications

| Displacement: | 5660 cc |

| Engine: | Supercharged eight-cylinder four-stroke in-line engine |

| Entered in racing: | 1937 |

| Top speed: | over 300 km/h |

| Output: | 592 hp (435 kW), later boosted to up to 646 hp (475 kW) |

Mercedes-Benz W 154

1938 to 1939

In September 1936, motor racing’s legislative body, the AIACR (Association Internationale des Automobile Clubs Reconnus), decreed the parameters of the new Grand Prix formula from 1938 onwards. The key elements: a maximum displacement of three litres for supercharged engines, or of 4.5 litres for naturally aspirated units, a minimum weight of 400 or up to 850 kilograms, depending on the engine’s displacement.

The 1937 season hardly had ended when the Mercedes-Benz engineers were already busy preparing the next with a host of new ideas, concepts and concrete steps. A naturally aspirated engine with three banks of eight cylinders each, i.e., a W 24 configuration, was considered, as were a rear-mounted engine, direct petrol injection and fully streamlined bodies. In the end, above all because of thermal reasons, the engineers opted for a 60-degree V12 developed in-house by specialist Albert Heess. In doing so, with 250 cc per combustion unit, they had again arrived at the minimum displacement in each of the eight cylinders of the supercharged two-litre M 2 L 8 engine of 1924. Glycol as coolant permitted temperatures of up to 125°C. Four overhead camshafts actuated 48 valves via forked rocker arms. Three forged steel cylinders at a time were united within welded-on coolant jackets. The heads were not removable. Powerful pumps pressed 100 litres of oil per minute through the engine which weighed 500 kilograms. Two single-stage superchargers were used initially, to be replaced by a two-stage supercharger in 1939.

In January 1938 the first specimen was running on the test bench, and the first almost trouble-free test run was completed on February 7, when the engine developed 427 hp (314 kW) at 8000 rpm. In the first half of the season, drivers Caracciola, Lang, von Brauchitsch and Seaman had 430 hp (316 kW) at their disposal, towards its end more than 468 hp (344 kW). In Reims, Hermann Lang’s car was fitted with the most powerful version with 474 hp (349 kW), howling down the long straights of the Champagne circuit at 283 km/h at 7500 rpm in his W 154. And for the first time a Mercedes-Benz racing car had five gears.

Max Wagner’s task in the suspension design department to come up with a suitable chassis was much easier than that of his colleagues in the engine department. He took over the basic architecture of the previous year’s state-of-the-art solution for the W 125 to a major extent but increased the frame’s torsional stiffness by another 30 percent. The V12 was installed deeply and at an angle, with the carburettors’ air intakes projecting out of the radiator whose grille was progressively broadened before the beginning of the season.

The driver was seated to the right of the propeller shaft. The W 154 cowered close to the tarmac, the body profile being considerably lower than the tops of its tires. This not only endowed it with a visually dynamic appeal but also suitably lowered its centre of gravity. Manfred von Brauchitsch and Richard Seaman, on whose technical expertise Chief Engineer Rudolf Uhlenhaut was able to rely, were at once taken with its road-holding qualities.

The W 154 had been the most successful Silver Arrow until that point in time: Rudolf Caracciola clinched the 1938 European champion’s title (a world championship did not yet exist), and the W 154 won three out of four Grand Prix races counting towards the championship.

In order to avoid problems in terms of weight distribution the balance was equalled out by means of a saddle tank above the driver’s legs. In 1939, a two-stage supercharger boosted the V12’s output to 483 hp (355 kW) at 7800 rpm. This engine was now called M 163. The endeavours of AIACR to reduce the open-wheel Grand Prix racing cars’ speeds to acceptable levels had practically failed. The fastest laps, for instance on Bern’s Bremgarten circuit, were almost identical in 1937 (still according to the 750-kg formula) and in 1939 (with the new-generation three-litre cars). In all other respects as well, the W 154 had been refined a great deal over the 1938/39 winter. A higher cowl line in the cockpit area provided greater safety for the driver. A small instrument panel in his direct field of vision was attached to the saddle tank. As usual, it gave only the most essential information, with a large rev counter in the middle, flanked by the gauges for water and oil temperatures. This was entirely in keeping with Uhlenhaut’s principles. The driver, he used to say, must not be distracted by an excess of data.

Technical Specifications

| Top speed: | 330 km/h |

| Displacement: | 2963 cc |

| Output: | 427 hp (314 kW), later boosted to 474 hp (349 kW) |

| Entered in racing: | 1938/39 |

| Engine: | V12 four-stroke petrol engine with two superchargers, 60 degrees, 1939 version with a two-stage supercharger |

Mercedes-Benz W 165

The Grand Prix teams’ favourite race in the 1930s was a race which did not even count towards the European championship: the Tripoli Grand Prix in Libya, an Italian province since January 1934. Its governor was bearded air marshal Italo Balbo, addicted to motor racing and other good things in life – and a brilliant host to boot.

The Tripoli Grand Prix simply was an attractive proposition for the teams. They were greeted by summer heat while Europe was still shivering with cold, an exotic ambience on white marble terraces and under palms, glittering parties and generous prize money, not least because Italy had been indulging in betting on place and win within the framework of a lottery since 1933. Small wonder, therefore, that the Grand Prix circus liked to come to Tripoli.

But in secret the organisers were quite annoyed that the last victory of an Italian racing car, an Alfa Romeo, dated back to 1934. Ever since, the Silver Arrows had been virtually subscribed to first places on the fast, 13-kilometre Mellaha racetrack, round the eponymous lake outside the city gates of Tripoli. The 1935 was won by Rudolf Caracciola. In 1937 and 1938 it was Hermann Lang’s turn driving the Mercedes-Benz racing car. In 1936 the winner had been an Auto Union racing car.

That nuisance had to be remedied. In 1937 and 1938 there had already been a separate 1.5-liter category to ensure Italian triumphs, at least in the lower echelons. Rumour had it that the Grand Prix formula from 1941 onwards might be for cars with the same displacement. To be suitably ahead of things but also to put a stop to the perennial German victories, the Italian motor sport authorities decreed a 1500 cc limit (voiturette formula) for their own open-wheel cars from 1939. Alfa Romeo with their Alfetta 158 and Maserati with their new 4CL were well prepared for this.

The new regulations were announced in September 1938.

Mercedes-Benz racing manager Alfred Neubauer was informed about this after the Gran Premio d’Italia in Monza on 11 September 1938. The 13th Tripoli Grand Prix was to take place on 7 May 1939. So there were less than eight months to come up with a new car – a race against time. It was, however, to end in outstanding triumph.

A first meeting of the men involved was scheduled on 15 September 1938. Max Sailer, ex-racer and chief engineer since 1934, shrugged off the objections raised by the design engineers that such a project was impossible to realise in view of the scant time. It had to be. On 18 November followed the official order by the management. By mid-February 1939 all the essential drawings by engine specialist Albert Heess and passenger car design chief Max Wagner were finished. In early April there was the first encounter between drivers Rudolf Caracciola and Hermann Lang and their new mount, one of two built, in Hockenheim, resulting in 500 almost trouble-free kilometres. To everybody’s surprise the final list of contestants issued by the organisers of the Tripoli Grand Prix on April 11 included two Mercedes-Benz W 165 cars – the brand’s first 1.5-liter racing cars since the Targa Florio in 1922.

The immense time pressure haunting the project inescapably triggered practical necessities. The W 165 obviously had to follow the lines established by the up-to-date W 154 Grand Prix car, which, of course, was being feverishly further developed at the same time. Indeed the open-wheel W 165 looked like a scaled-down version of its big brother, 3680 millimetres long (W 154: 4250 millimetres) and with a shortened wheelbase of 2450 millimetres (W 154: 2730 millimetres). The braces of its tubular oval frame consisted of nickel chromium molybdenum steel, its five cross members being complemented by the rear engine support. The driver’s seat was slightly offset to the right, and so were the windshield and the rear-view mirrors. As on the W 154, the propeller shaft was angled though, because of the cramped conditions, it had been impossible to create the space for the customary central position. What’s more, the seat was positioned farther forward, as Wagner wanted to stow away as much petrol as possible within the confines of the wheelbase. Again there was the tank in the tail, as well as a saddle tank above the driver’s thighs. Topped up but without its driver, the W 165 weighed a mere 905 kilograms, 53.3 percent of which were placed above the rear axle.

The engine, weighing just 195 kilograms, could not deny its kinship with the W 154’s V12. It was a compact 1493 cc 90-degree V8 with four overhead camshafts and 32 valves, its valve gear and arrangement being almost identical with the Grand Prix engine’s. Its right-hand bank was offset forward by 18 millimetres, either bank consisting of four combustion units sharing a common base plate and (glycol) coolant jacket. The heads were welded together with the cylinders. Tests with a centrifugal supercharger were discontinued as boost pressure dropped quickly at low revs. So the mixture formation system was made up by two Solex suction-type carburettors, powerfully assisted by two Roots blowers. Its 254 hp (187 kW) at 8250 rpm were equivalent to a power-to-swept-volume ratio of 170 hp (125 kW) – indeed an impressive value. Their taming had been efficiently looked after as well, as huge brake drums (with a diameter of 360 millimetres) filled almost the complete interior of the wire wheels. Even the heat of the Libyan host country (52°C on racing day) had been allowed for in that the fuel feed lines were guided through a tubular radiator.

The rest is racing history at its very best. The Mercedes-Benz W 165 cars gave their opponents no break. Caracciola, on fresh tires, raced right through with his short-ratio car, while Lang with his “long” rear axle ratio (and thus a higher top speed) made one quick pit-stop and won the Tripoli race almost one lap ahead of his team-mate. He might have lapped him but then his scruples prevailed – one cannot do that to this man. Times were different then.

Technical Specifications

| Top speed: | 272 km/h |

| Displacement: | 1495 cc |

| Output: | 254 hp (187 kW) |

| Engine: | V8 four-stroke petrol engine with two superchargers, 90 degrees |

| Entered in racing: | 1939 |